A quick comment on the "slippery slope fallacy" that usually isn't

Plus a few comments at bottom regarding Christianity and the bio-surveillance regime

Let me give you the big conclusion up front today and then we’ll go through the conversation that ended here. What is derided today as the “slippery slope fallacy” or “slippery slope fearmongering” is often actually a reasoning process going through one of the two following (and related) routes:

Recognizing the assumptions that motivated action A, and using that recognition to predict that actions B and C would logically follow in the future from that same assumption.

Noticing that other places, in history or around the world, that did A and B later did C, and so suggesting that if we do A and B, it’s likely that we would eventually do C as well.

Far from being fallacies, both of the above actually describe someone thinking well. As the good James David Dickson said:

OK, why is this on my mind today? Had a little Twitter conversation with a reporter from Illinois, motivated by this tweet:

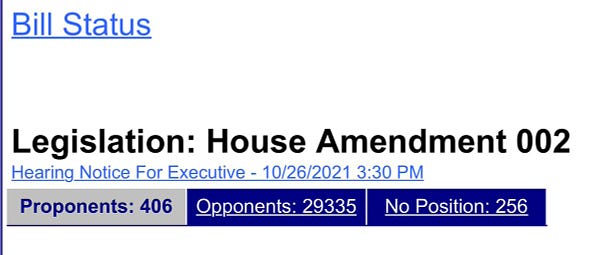

This is actually great news. I had a post on this Illinois law actually ready to go for today but I was advised to see if another publication wanted it instead… maybe you’ll get it in a few days. But suffice it to say for now that Illinois has a great law, from 1998, that is quite all-encompassing and prohibits you from forcing medicine on people if they have a conscientious objection to it, or discriminating against people on the basis of their medical choices. It’s the sort of law that would have been non-controversial before yesterday. The law has been rediscovered by people resisting vaccine mandates and testing requirements (because the 1998 law specifically mentions even that you can’t compel people into testing), and therefore the governor and legislature are now undertaking steps to revise the law to nullify people’s efforts to use it to decline COVID-19 vaccination or testing. As you can see there, nearly all of these 30,000 comments are from people against the revision of the law.

Here we also see a legacy media reporter referring to people standing up for conscience rights that would have been uncontroversial before yesterday as “anti-vax”, and I did mention that. To my surprise, the reporter engaged with me.

We will have some more comments on that second question in a moment here. But I replied to say that if, in a month from now, the testing alternative was removed (a path we have actually seen followed elsewhere), this reporter would not suddenly then become concerned about conscience rights. “We want A, not B” these days is just a brief prelude before “we want A, B, C, D, and E”.

I will accept the correction that I don’t know this reporter very well, OK. But finally the accusation of “slippery slope… fearmongering”… but it’s not. It’s noticing what has happened elsewhere, and it’s knowing what assumptions and (lack of belief in any limits to its power) motivate the actions of the technocracy. Hence,

And I have to throw in Arne Christensen’s comments from later, especially since he often reads these posts.

And one more from the good ArchibaldHeath1,

OK. A few final comments here on the “what religious objections could there be to regular testing?”. There is plenty you could say there, particularly about the whole idea of orienting an entire society around medicine and health, and taking part in the rituals that affirm that orientation, a idolatry Christians should reject vehemently. But two smaller objections could also be made:

First, the one we’ve already made, there is abundant reason to believe that “do A or, if you have a problem with it, B” is just a stepping stone to “actually you have no choice but to do A”. Boil the frog slowly. We’ve seen that happen too many other places already. The technocrats don’t actually believe in conscience rights (Trudeau in Canada seems quite proud of the fact that it’s virtually impossible to be exempted from his vaccine requirements). No conditions that could be met that would make the testing requirement go away are ever articulated by the perpetual-emergency state. The frog would be wise to object now instead of objecting later.

Perhaps more importantly, “must participate in corporate medical product just to exist in society” is absolutely a claim Christians should reject. That has never been the rule before and it shouldn’t be the rule going forward.

"This external technological instrument determines whether one may participate in society" is objectionable to me as a Christian, as an American, and as someone who knows history. Also, no points for beginning the argument by implying your interlocutor is irrational.@david_shane It’s almost like you’re mad at how accurate the description was. Though I described the FB groups, not the individual people filling out slips. Also, would you care to describe what religious objection might bar you from taking a simple spit test to make sure you’re not sick?

"This external technological instrument determines whether one may participate in society" is objectionable to me as a Christian, as an American, and as someone who knows history. Also, no points for beginning the argument by implying your interlocutor is irrational.@david_shane It’s almost like you’re mad at how accurate the description was. Though I described the FB groups, not the individual people filling out slips. Also, would you care to describe what religious objection might bar you from taking a simple spit test to make sure you’re not sick? Mark Maxwell @MarkMaxwellTV

Mark Maxwell @MarkMaxwellTV

There are really two different ways that an argument might make an appeal to a "slippery slope". The first is an actual argument that some slope really is slippery, and that failing to draw a line at the current issue will make it harder to do so in the future, since it concedes a broad principle that will be incorporated in a larger epistemic model that can be deployed in more extensive ways. This is what Scott Alexander used to call "building a superweapon", where failing to defend several weak hills against a moderate and reasonable line of attack makes it more difficult to defend a strong hill against unreasonable attack in the future, when it really matters.

The second is just an appeal to consistency. When someone makes an argument based on an appeal to a principle that, if followed through consistently, would result in all kinds of obviously wrong conclusions, then we have a good basis to doubt that principle is valid. This can look like appealing to a slippery slope, but really what you are saying is more like, "Thank goodness this slope isn't actually as slippery as it should be, since to my immense relief you are a hypocrite. But you are appealing to a principle that, if a consistent person did believe it, would be deeply alarming in consequence."

Calling both of these things "the slippery slope fallacy" is the cause of all manner of confusion.

My comment was a little flippant, but on point. Can't Maxwell see that maybe people would object to having no say at all on whether or not they have to take "a simple spit test"? That they might want to take part in the democratic process and have the legislature legislate, rather than submit to the governor?