What we wondered at, now is boring

A few thoughts, and a link to an Astral Codex Ten piece you should read

As you may know, the Fram2 mission splashed down off the coast of California on Friday (four humans, polar explorers, civilians, who orbited around the poles of the Earth for a few days, all paid for by Chun Wang, a cryptocurrency tycoon). I showed students the livestream of the splashdown and recovery actually, and a few seemed to find it quite inspiring, also with a “how cool would it be to work there?!” vibe. (I’m sending you future employees, SpaceX… well, you never know.) You do have moments, like before parachute deployment… oh, the capsule is just falling to Earth right now, literally just falling miles and miles through the sky. That’s kind of terrifying.

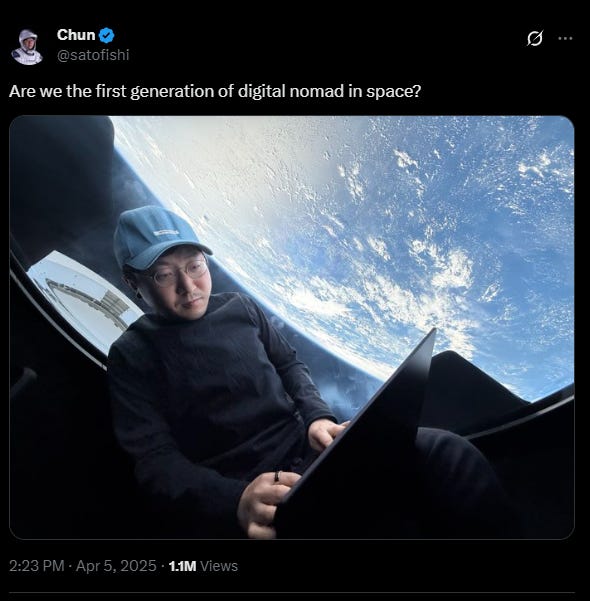

The mission commander shared this photo on his Twitter account.

Now, don’t worry, I’m sure Chun spent a ton of time during the flight just looking out the window. But this one photo, anyway, I couldn’t help but think - he’s got the beauty of the planet right behind him, a view 0.00000058% of humans have had available to them (yes, I did the math), and he’s looking down at a tablet instead doing something on the internet (they had internet access via Starlink). Of course you think about the way most humans fly in aircraft today, also with views out the window that would have astounded, at least at first, almost every human, and they close the shades and go to sleep. We make wonders cheap and then very quickly they cease to be wondrous to us, unless an intentional effort is made (or perhaps you have just the right personality… or degree of sanctification).

And that is somewhat what this Astral Codex Ten piece (Scott Alexander), titled The Colors of Her Coat, is about (because blue/purple dye also was once very difficult to obtain), also as applied to new AI technologies… which, for example (don’t fight me about definitions right now) will make art that might have taken months of work and been hung in art galleries in the past, now, in just a few seconds, and what does that mean for how we humans will respond to it? I’ve had this thought about Heaven before myself:

If I can frown and walk past a canvas painted in pure ultramarine, would I also grow weary of green wine and crimson seas? If I went to Heaven, surely the first few days would be pretty great. But would I eventually walk past golden mountains and silver trees and crystal ships on crimson seas with the same nonchalance with which I walk past granite mountains / wooden trees / etc today?

And later, speaking of wonders all around us we already don’t notice:

My lack of appreciation for ultramarine dye is of the same kind as my lack of appreciation for not dying of cholera. Or for coffee - an ordinary latte might blend beans from Ethiopia, Ghana, and Suriname with sugar from Brazil and vanilla from a rare orchid found only in Madagascar; by now, it’s so unbearably boring that you can find dozens of Reddit threads asking how to spruce it up, make it feel new again. We gripe about how LLMs are destroying wonder, never thinking about how we’re speaking to an alien intelligence made by etching strange sigils on a tiny glass wafer on a mountainous jungle island off the coast of China, then converting every book ever written into electricity and blasting them through the sigils at near-light-speed. It’s all amazing, and we’re bored to death of all of it.

This has hitherto been slow enough to tolerate, but strong AI will make it all worse. You will see wonders beyond your imagination, nod, think “that’s a cool wonder”, and become inured to it.

I don’t want to quote much more, so I’ll direct you to the whole piece for your attention, including his conclusion. Another very relevant question would be, since this is the world we live in, what are the implications for how we should teach students in an effort to preserve wonder for and in them? (I might actually do one thing just by reading them Alexander’s piece.)

People are getting less imaginative. We can speculate about the various reasons why, but consider those Medieval and Renaissance maps with made-up continents, made-up peoples, etc. Or the long-held belief, absent any solid evidence, in life on the Moon, or Mars, other planets.

Of course those mapmakers were recklessly speculative, but they had a robust spiritedness that isn't very apparent in the culture now.

I agree to an extent, but I think the horizon of wonder has simply expanded further, as we’ve gained greater understanding of the natural world. (And even the things we do understand still prompt an awful lot of wonder—ever stood on your porch and watched a thunderstorm approach?) Maybe orbiting around the planet and looking out the window doesn’t evoke the same kind of wonder it once did (at least, imagining what it would be like) but what about orbiting around a black hole? Watching a supernova?

There’s are still plenty of absolutely amazing things out there to experience, and the mysteries of the universe aboard. We keep peeling back the layers of Creation only to discover more that was hidden from view!